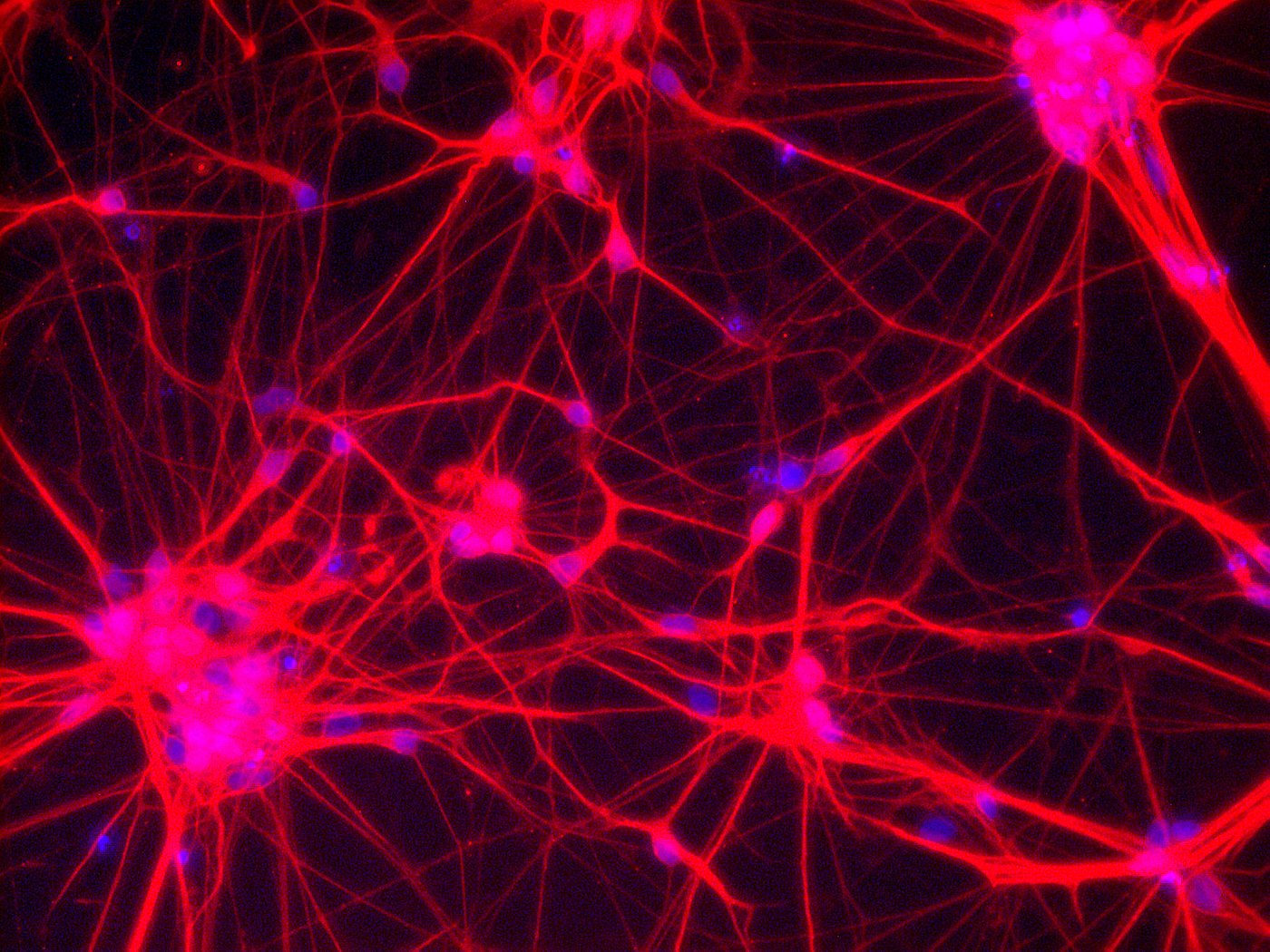

Neurons – Network of neuronal cells (Blue: nucleus; Red: neurons) [Copyright: Institute for Transfusion Medicine, UK Essen]

Scientists have already been able to produce functional egg and sperm cells in mice using pluripotent stem cells, which can be derived from skin. Following fertilization, these egg and sperm cells are then able to develop into viable offspring. However, it is conceivable to extract both germ cell types – i.e. both egg and sperm cells - from the body cells of one animal and by and large this has already been achieved in animal experiments.

This new study (Nature, doi: 10.1038/nature20104) represents important progress insofar as it is the first time that it has been proven to mature egg cells derived from stem cells completely in vitro - i.e. in the petri dish. Up until now, the final maturation steps could only take place once the germ line cells (derived from stem cells) had been implanted back into the body of a lab animal. If it is possible to transfer the process developed on mice to humans, in the long term, this could make it possible to produce almost unlimited amounts of egg cells from body cells, although the current Nature study also shows that there are clearly still differences in the quality of the egg cells produced. Such a scenario could have disruptive consequences for reproductive medicine and for our basic understanding of human reproduction.

The limited availability of egg cells and the inconvenience and health risks associated with obtaining them are currently considered to be a decisive limiting factor in reproductive medicine. If it were one day possible to produce large amounts of egg cells from body cells without risk or pain, artificial insemination could become interesting or more promising for significantly more women, particularly in a higher age bracket, once natural fertility declines. Egg cell donation, which is controversial for many reasons and is still banned in Germany, could become unnecessary.

In countries with more liberal legislation, at least, the large-scale use of pre-implantation diagnostics would be conceivable. If very large amounts of egg cells developed from body cells were to be fertilized and genetically analyzed, it could be possible to significantly increase the number of selectable ‘desired’ traits - a 'designer baby’ scenario. In Germany however, this kind of mass production and selection of embryos is currently prohibited.

Given that when germ cells are developed from body cells, it is conceivable that sperm could be produced from the cells of a woman and egg cells from the cells of a man, yet more new possibilities are emerging on the horizon in addition to the already broad spectrum of unusual reproductive constellations. Not only female, but also male gay couples could have children together which are genetically theirs - although men would still have to rely on a surrogate mother, which is currently banned in Germany. Even children with only one parent would be conceivable, created from the artificially developed egg and sperm cells of one single person, yet they would not be clones. The German Ethics Council has already indicated some of these challenges in its ad-hoc recommendation from 2014 entitled ‘Stem Cell Research – New Challenges for the Ban on Cloning and Treatment of Artificially Created Germ Cells.’

For science, the process could ultimately make research with embryos and embryonic stem cells easier. Germany, however, prohibits research on embryos and the destruction of embryos for the purposes of producing embryonic stem cells. But even in countries with a more liberal legislation, the fact that research is reliant on donated egg cells is cited as a critical argument against embryonic research. This criticism would become groundless with the new method, if it could be transferred to humans. There would be an almost endless supply of egg cells.

All this shows that the scope for options in technical reproduction could expand dramatically; many moral, social and legal challenges would arise from these possibilities. Reproduction in the age of increased technical reproducibility would in turn become less matter-of-course.

But even now, the seemingly ever easier methods of producing functional germ cells from normal adult cells should encourage reflection in Germany too on whether our current legislation is still adequate for protecting the earliest stages of human life. We should ask ourselves in all seriousness whether in future we ought not to base our decisions to prohibit such matters on the respective contexts of responsibilities (research or reproduction) and not – as we have up until now – based abstractly on ontological boundaries. As this current research on mice shows - these boundaries appear to be getting more and more fragile.

Professor Peter Dabrock

Professor of Systematic Theology II (Ethics), Friedrich-Alexander University of Erlangen-Nuremberg

Chair of the German Ethics Council (www.ethikrat.org)