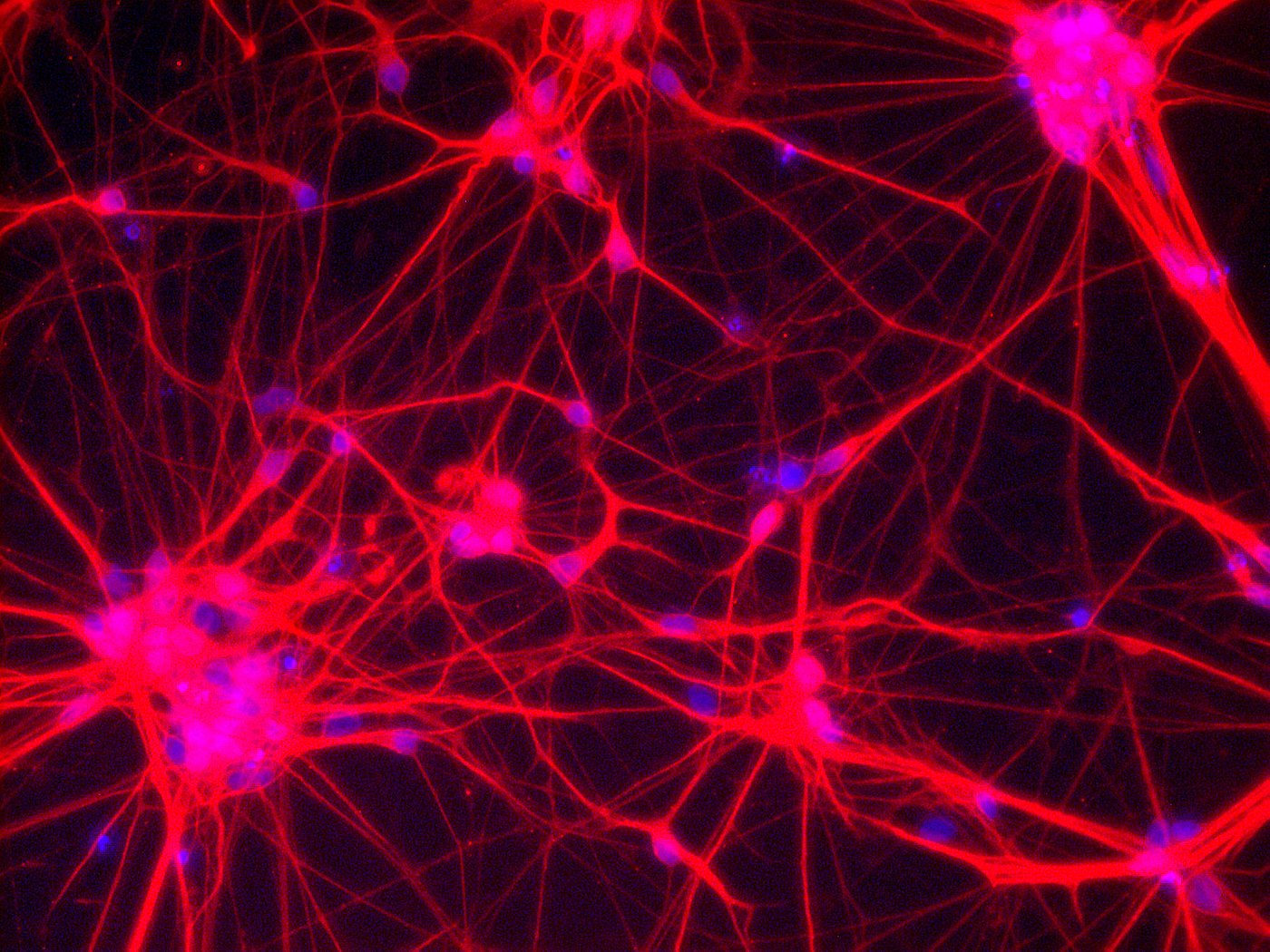

Neurons – Network of neuronal cells (Blue: nucleus; Red: neurons) [Copyright: Institute for Transfusion Medicine, UK Essen]

The call was co-authored by bioscientists (including Eric Lander, Emmanuelle Charpentier and Feng Zhang) and bioethicists (including Françoise Baylis and Bettina Schöne-Seifert, board member of Stem Cell Network NRW). It forms part of a debate on the societal consequences of changes to the human genome which is gaining momentum due to rapid scientific advances and became widely publicized in November 2018 in the wake of the birth of genetically modified babies in China.

CRISPR/Cas and Heritable Genome Editing

Based on seminal research by, among others, Jennifer Doudna (UC Berkeley), Emmanuelle Charpentier (MPI Berlin) and Feng Zhang (MIT), the so-called CRISPR/Cas method for genome editing has gained considerable currency since 2012. This technique greatly simplifies the production of so-called "genetic scissors" that allow for very precise changes to the genome. CRISPR/Cas has caused quite a stir in science and the media. To some extent, this is because the method has great potential for the treatment of diseases: For instance, the genome of blood stem cells could be manipulated to the effect that the cells generated by these blood stem cells are immune against certain illnesses. However, the most intense controversy surrounding the new technique is owed to the fact that not only body cells (so-called somatic cells) can be edited, but also cells of the germline, such as sperm and egg cells. In contrast to changes in somatic cells, genome changes in germline cells are heritable. Such interventions could potentially eradicate diseases that are due to specific genetic traits in edited individuals and their descendants. It was this kind of genome change that triggered reactions ranging from surprise to shock in the fall of 2018: In order to reduce the risk of HIV infections, Chinese biophysicist He Jiankui had deactivated the gene CCR5 in embryos produced via in vitro fertilization. CCR5 encodes a protein that allows the HI virus to enter the cell.

Many scientists and ethicists consider these experiments to be irresponsible. The deactivation of CCR5 may increase the risk of other diseases and, in general, too little is known about the effects of the procedure to employ it in humans. Above all, they are concerned because the widespread production of genetically modified children could have grave societal consequences. It is conceivable, for instance, that parents would experience pressure to have their offspring edited in certain ways. People with genetic disabilities may face increased discrimination. Should access to beneficial genomic changes depend on ability to pay, economic inequalities could become genetically reinforced.

Against the background of such concerns, the authors call for the cessation of any research that generates genetically modified babies. Thus, the appeal exclusively targets inheritable manipulations of sperm, egg cells or embryos, but not genome modifications in somatic cells, which are not transmitted to offspring. Likewise, altering the genome of germline cells for research purposes (i.e., without the goal of producing a living organism) should remain possible.

Moratorium and International Regulation of Genome Editing

All heritable alterations to the human genome are initially to be suspended for a fixed period of, e.g., five years, while further research efforts are directed at important open questions. In addition, bodies and procedures are to be set up that coordinate the approval of possible future genome editing in clinical contexts.

In terms of open questions, the authors list various examples. For instance, they discern a need for research into the risk of unwanted mutations and the long-term consequences of genome editing for the modified individuals. The issue whether corrections of individual mutations that are likely to cause certain diseases should be treated differently from broader interventions that aim for a variety of "enhancements" also requires clarification. Since the implications of heritable genome editing are potentially far-reaching and numerous uncertainties persist, scrupulous comparison of any proposed application to alternative methods is in order.

In terms of establishing an international framework for the regulation of heritable genome editing, nations are supposed to initially commit themselves to the observance of the temporary research ban. After the moratorium has expired, they can, in principle, permit clinical applications of genome editing, given that certain conditions are met. These include that experiments will be publicly announced in advance and discussed internationally for a sufficiently long period of time. In addition, the respective project should be evaluated transparently in terms of its scientific, medical, social and ethical aspects, and a broad societal consensus regarding its appropriateness is to be ensured. To support the nations, a coordinating body should be established, conceivably tied to the World Health Organization (WHO). A committee of experts in biomedicine, ethics, and social sciences should report on new developments on a regular basis.

Responses to the Call

In accordance with the call, many experts believe that heritable interference with the human genome should at present be suspended, and that a broad societal debate must first take place. However, views differ as to whether the proposed moratorium is necessary or helpful. In about 30 countries including Germany, the corresponding procedures are already prohibited. By contrast, as a voluntary commitment by nations, the moratorium itself does not ensure that violations will be prosecuted. Therefore, it is doubtful whether it would have prevented He's experiments in China. On the other hand, scientists fear that stopping research for a fixed period may make it difficult to respond flexibly to new developments, thereby delaying desirable progress. At this time, it is unclear to which extent the call will be heeded. While the US National Institutes of Health explicitly support the call, the UK Royal Society, the US National Academy of Sciences, and the US National Academy of Medicine are slightly more reluctant. Also, one of the pioneers of the CRISPR/Cas method, Jennifer Doudna, has not signed the appeal, unlike her former colleague Emmanuelle Charpentier and fellow pioneer Feng Zhang. Instead, Doudna supports efforts by various national science academies to develop internationally accepted standards for the application of heritable genome editing. This initiative, in turn, interacts with a committee set up by the WHO in December 2018 which aims to formulate recommendations for governance and monitoring of human genome editing over the next two years. As early as May 2019, the German Ethics Council intends to issue a detailed statement on germline interventions.

Full text of the call for a moratorium: Lander et al., Adopt a moratorium on heritable genome editing, Nature Comment, 13.03.2019

Newspaper coverage and expert statements:

Scientific publications: