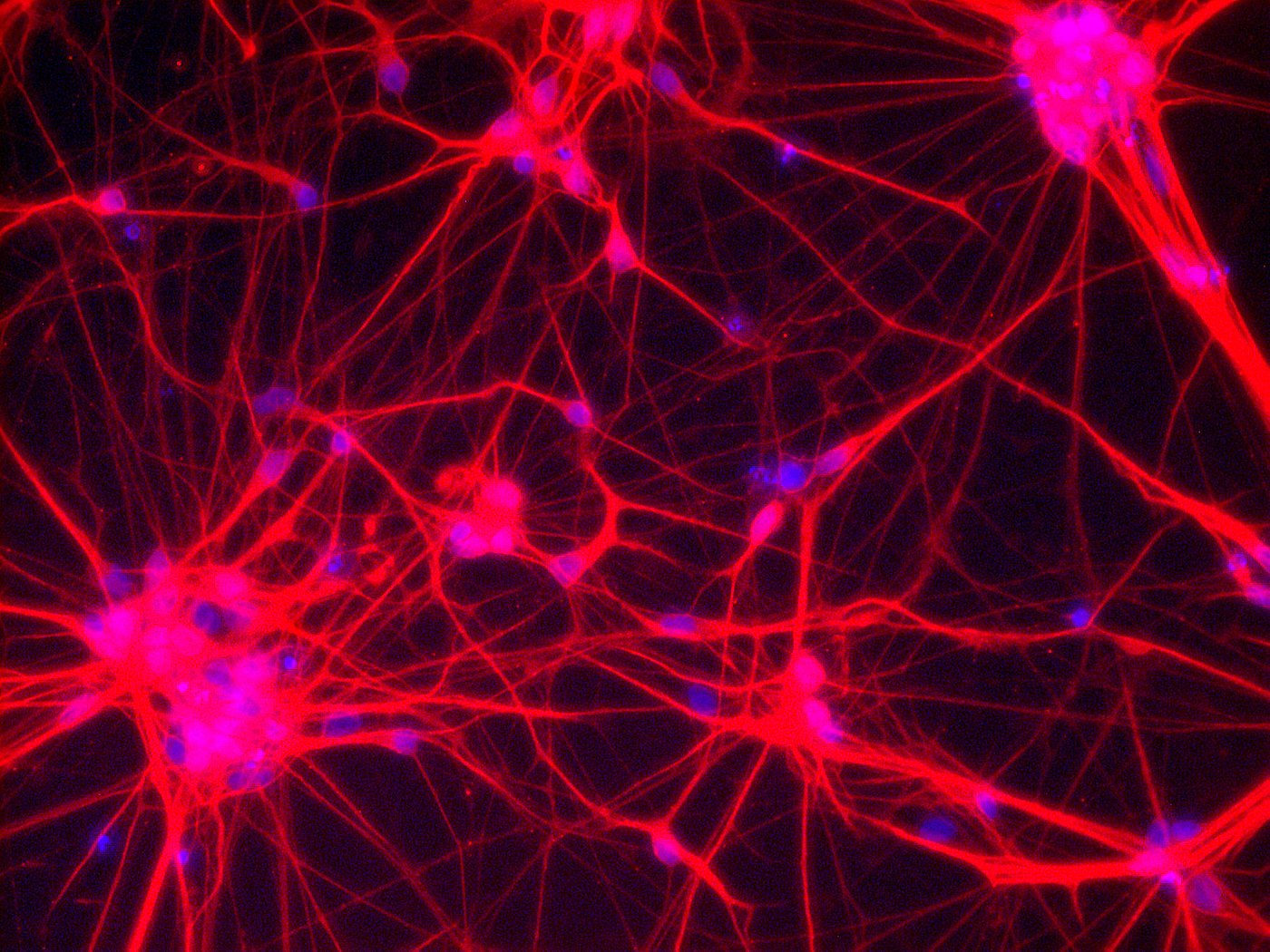

Neurons – Network of neuronal cells (Blue: nucleus; Red: neurons) [Copyright: Institute for Transfusion Medicine, UK Essen]

In many countries across the world, unproven stem cell-based treatments are a reality that the legal system has to grapple with. The regulatory authorities are confronted with a scientifically and normatively complex topic. Overseeing and evaluating this complicated issue is extremely difficult for the actors, for whom it is usually only one of many topics in their area of responsibility. Regulatory bodies are confronted with actors on the provider side who concentrate on a narrowly defined business model and are able to put a lot of effort into identifying legal gray areas and formulating marketing strategies.

The article “Challenges in the Regulation of Autologous Stem Cell Interventions in the United States”, published in Perspectives in Biology and Medicine Vol. 61 (2018), tries to give a better overview of this complex field. Author Douglas Sipp first of all notes that the market for unproven stem cell-related treatments has undergone fundamental changes in many respects in recent years. The two most important developments include that

(1) there are an increasing number of suppliers in highly developed countries such as the USA, Japan and Australia and

(2) suppliers are increasingly concentrating on autologous treatment approaches compared to the previously very broad spectrum of stem cell sources.

According to the author, the majority of providers who advertise unproven stem cell-related treatments in English have their headquarters in the USA. Against this background, Sipp analyses the regulatory situation in the USA and focuses in particular on three supplier strategies.

The first of these strategies aims to evade supervision by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) by invoking the Same Surgical Procedure Exception. In Section 15b of the Code of Federal Regulation 1271, which regulates drug approval at federal level, treatments are excluded from FDA control if cells are removed and also implanted back into the donor during the same surgical procedure. This provision is similar to the so-called hospital exemption of Article 28 (2) of the ATMP Regulation (1394/2007/EC), which applies to all Member States of the European Union. This allows an exemption from the central approval procedure via the European Medicines Agency (EMA) if cell preparations are prepared individually for a patient, not routinely produced, and are administered in a clinic under the supervision of a physician. In the USA, more and more providers are relying on the Same Surgical Procedure Exception and, according to the author, there are indications that the FDA will apply stricter interpretative measures in the future to better control the growing market for unproven stem cell-related treatments. However, the author is skeptical whether these efforts have a chance of success in view of the expected legal resistance of the providers and also the fundamental line taken by the Trump administration in such matters.

A second strategy, which is increasingly used by providers in the USA, is aimed at marketing treatments no longer as for therapeutic use but as research. Interested parties are given the opportunity to participate in a clinical study for a financial contribution (which is on the same scale as treatments offered by other providers). Such “pay-to-participate” or “patient-funded” studies have the advantage of a reduced liability risk for the providers. As effectiveness of the treatment is not promised due to the research character of the project, the risk of being sued for lack of treatment success is also reduced. In addition, not all clinical trials registered in the USA via the National Institutes of Health (NIH) are subject to close professional supervision by the FDA. The author points out that the partially lower standards of protection in privately financed clinical studies, together with the lower liability risks, represent a favorable starting point for dubious offers. Many providers may find it attractive to shift their business model from treatment to “pay-to-participate” studies. This has a number of problematic implications. First of all, such a business model provides incentives to design the studies in a way that results in no valid statements about the effectiveness of the approaches. It is also to be feared that such studies will poach participants from clinical trials that have a better research design and are therefore more relevant for research.

The third strategy described in the article is the increasing marketing of autologous stem cell treatments as “personalized care”. The choice of words ties in with the enormous potential of personalized medicine, which also plays an increasingly important role in serious scientific discourse. Potential customers associate this with the promise of personal and customized provisions; a very promising choice of words from a purely advertising-psychological point of view. At the same time, this strategy offers the possibility of protecting processes against scientific counterevidence and thus also liability claims. It could be argued that a personalized treatment plan cannot be refuted by a generalized scientific study, as it cannot by definition capture the peculiarities of the individual person. Such individualized treatments could be presented as clinical studies with only one subject and any objection to them could be invalidated by referring to individual factors.

Each of the provider strategies mentioned in the article is tailored to the USA and its specific legal situation. They are attempts to minimize legal risks (in particular liability risks) for providers under the conditions of a specific legal system. Just as these strategies cannot be applied one-to-one to the regulatively very different field within the European Union, the marketing trends among providers of unproven stem cell-related treatments in Europe will also be different. One of these differences would be the (recently observed in Europe) approach of no longer offering treatments with stem cells themselves, but with so-called “curative factors extracted from stem cells”.

Although provider strategies are very different in different legal systems, it is important to keep an eye on trends in provider strategies even outside your own legal system. This is the only way to create long-term transparency in the growing market for stem cell-related negotiations in order to enable patients to make well-informed decisions about treatment options.