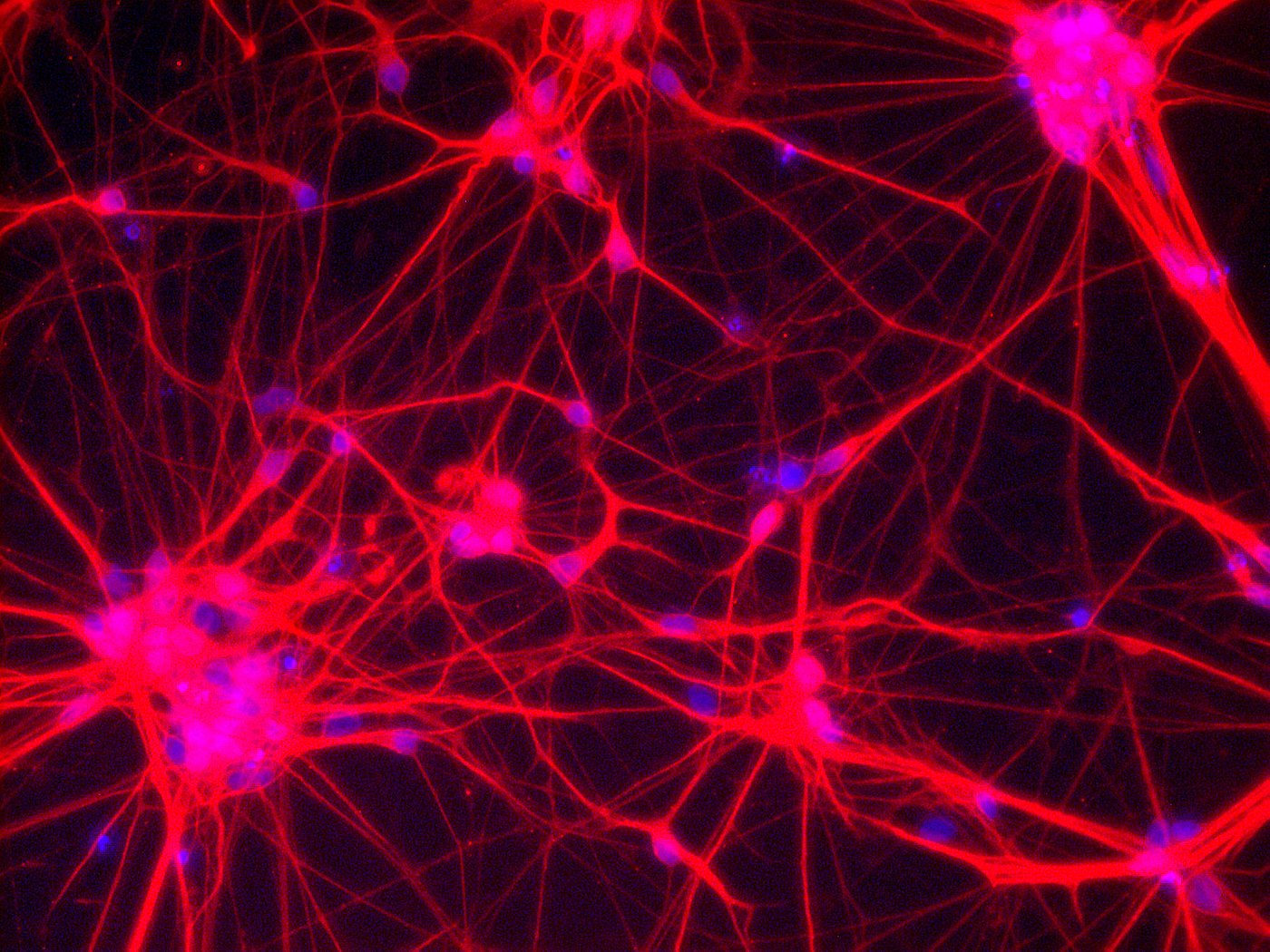

Neurons – Network of neuronal cells (Blue: nucleus; Red: neurons) [Copyright: Institute for Transfusion Medicine, UK Essen]

The unusual abbreviation CRISPR-Cas9 (CRISPR - Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats; Cas9 - Protein) stands for a process which can alter the building blocks of DNA in our genetic make-up. In the world of genetic engineering this is considered revolutionary – and yet it is not without controversy. Two experts from the fields of ethics and natural sciences respectively give their view in a joint interview: Dieter Sturma, Professor of Philosophy with particular regard to Ethics in the Biosciences at the University of Bonn and also, among other roles, Director of the Institute for Science and Ethics (IWE); he is joined by Michael Hölzel, Professor at the Institute of Clinical Chemistry and Clinical Pharmacology at the University Hospital Bonn. His working group is researching how cancer cells become resistant to new cancer therapies.

Why is CRISPR-Cas9 such a revolutionary technology – what sets it apart from other technologies?

Professor Hölzel: The system originates from bacteria, which are able to protect themselves against invaders (known as bacteriophages), i.e. a type of immune system for bacteria. As a result of ground-breaking work in recent years, researchers have been able to decode the mode of action, thus making the process accessible to broader biomedical research and paving the way for widespread application. With CRISPR-Cas9, the double-stranded DNA can be precisely cut at a specific place using an enzyme, which can be sequence-specifically guided into place with the help of a small RNA molecule. As a result, unlike other technologies, this produces a stable genetic modification with a similarly simple system. Or to put it more precisely, it is possible to modify any region in the genome, allowing us to potentially correct pathological mutations. This is one of the most central discoveries of the past few years, bringing with it completely new opportunities.

What is the probable impact of their application?

Professor Hölzel: Within the shortest space of time, CRISPR-Cas9 has become a standard process in biomedical research worldwide. In public discussions, this fascinating technology is often brought into connection with terms such as 'designer baby', i.e. aspects targeting the modification of genetic information in the germ line. In my view, it is important that CRISPR-Cas9 is primarily seen as a revolutionary contribution to fundamental biomedical research and to research in the pharmaceutical field. In cell cultures, it allows us to examine more precisely how drugs impact on certain genetic products and it also enables us to identify new approaches for drugs. In clinical use, CRISPR-Cas9 will certainly have a huge impact on cell therapy. For example, genetic defects in patients’ bone marrow cells could be corrected in vitro. The patient could then be given back his own bone marrow cells – potentially, a significantly more compatible alternative to transplanting healthy donor bone marrow cells, which the body could reject.

Why is there controversy between researchers of CRISPR-Cas9 - what are the ethical concerns?

Professor Sturma: The process makes it possible to intervene in the genetic makeup of a human being. Whenever basic research focusses on genes or embryos, people are often quick to evoke nightmare scenarios in ethical debates. They then start talking about interfering with creation, crossing natural barriers or allowing the floodgates to burst open, meaning that there will be no holding back the tide. I don’t share these opinions and am generally sceptical of a categorical ban on technological innovations. I find the argument of naturalness quite unhelpful – almost nothing that surrounds us is ‘natural’ anymore and the genetic makeup of humans has also changed throughout the history of the shift from nature to culture. In and of itself, biotechnology does not violate human dignity.

What is your view of this process?

Professor Sturma: I think it opens up a huge field of application, which must be fully explored in terms of its potential to create new treatments. In my opinion, there is no risk of the slippery slopes. On the basis of our biological, technical and normative knowledge, we are able to decide on a case by case basis how to deal with this process. The many opportunities revealed by this process do not have to be implemented right away. We can approach them slowly and steadily, with a high degree of vigilance. In current discussions, this approach can be observed in the work of the two pioneers of the process, Emmanuelle Charpentier and Jennifer Doudna.

How can we handle the CRISPR-Cas9 technology so as to adequately accommodate both the interests of research and the concerns of society?

Professor Sturma: What's important for me is the give and take of reasons in international ethical discourse. We mustn't forget that in other cultural environments, for example, humans are not seen as made in the image of God. There are differing normative attitudes that we have to take into account. During the biotechnological development, the therapeutic benefit, safety and controllability of the process must always be our top priorities. It is particularly crucial to clarify which medium to long-term consequences or side effects cannot be ruled out. We also have to take into account problems that arise from a potential commercialisation of the process.

Professor Hölzel: Before we can use the technology for treating humans, the process must be carefully validated to ensure that the DNA cannot be cut in other places as well (off-target cuts). We must optimize the precision of the cut. Studies must determine that an improved process only brings about the desired changes and does not create any others. Intensive basic research is still needed in this field and, subject to data, clinical trials could follow. Like all clinical trials, permission must be granted prior to the research by the Ethics Commission. The issue of modifying the germ line must be examined as part of a broad social discourse, as all wide-ranging aspects have been in the past.